Following the Line

“I came out of Bataan and I shall return,” MacArthur said on the platform of the Terowie Station, after his contentious retreat from the Philippines.

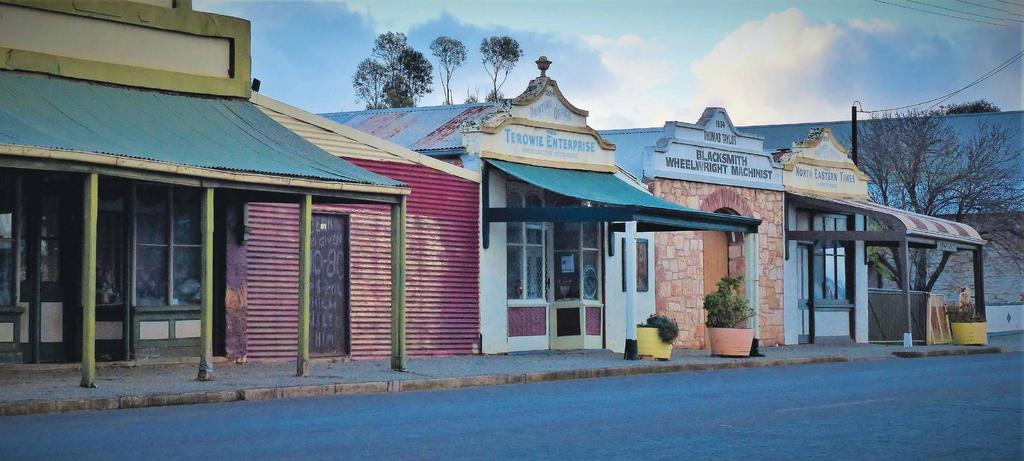

Today Terowie, 64km north of the old copper mining town of Burra in South Australia’s mid-north region, looks like a movie set — so much that you almost expect to see a horse and buggy trundling along the empty main street.

Known as ‘The Hub of the North’ during its halcyon days as a major railway town that was home to some 2000 people, these days Terowie has a population of around 130.

Settlers flocked here from the 1870s despite warnings from SA Surveyor-General George Goyder, who, in 1864-65 following a devastating drought, advised the colonial government to discourage farmers from planting crops north of a line delineating 30cm annual rainfall. This became known as Goyder’s Line.

Regardless of the drought and Goyder’s dire predictions, a succession of misleadingly green seasons in the 1870s encouraged farmers to venture beyond the regions of reliable rainfall, and a land boom erupted in what was supposed to be the utopia of the north.

The railway arrived in Terowie in 1880, when a broad range track ran from Adelaide, and a narrow-gauge line led to Peterborough, Quorn, and on to Broken Hill. The town’s hectic railway yards extended for almost 3km; the Terowie Hotel thronged with thirsty drinkers, teetotallers gathered at the Coffee Palace, shops were busy, and as many as 50 horse and bullock teams lumbered along Terowie’s streets in one day.

But Goyder was soon proven correct — settlement in this area was pretty much a disaster and very few made a go of farming.

A time capsule of a once-flourishing township, Terowie is one of a few towns in South Australia classified as a historic town for its almost untouched 19th century buildings.

Today the town’s old railway station and yards attract railway enthusiasts, as well as World War II buffs — an Army Staging Camp was established here as temporary digs for up to 1000 Australian and American troops. All that remains is an army prison cell block.

From Terowie it's 23km north-west to Peterborough, once another vitally important railway town.

Peterbrough was established in 1878 as a crossroads linking north, south, east, and west. In 1880 railway lines linking Port Pirie and Adelaide were opened to much fanfare, followed by the line to Orroroo to the north, and on to New South Wales. But dithering governments couldn’t agree on a standardised railway gauge, so three gauges — broad, standard, and narrow — led out of town.

Carriage of ore from Broken Hill to smelters at Port Pirie were the major contributor to rail traffic through Petersburg. In 1923 alone, 102 trains passed through Peterborough Station in one 24-hour period.

We learn this at Peterborough’s interesting Steamtown Heritage Rail Centre, once part of a vast railway operation, where you can tour original workshops, see the 27m-long triple-gauge turntable, and some classic engines and carriages, many from the original Ghan.

After dark visitors can watch Steamtown’s Sound and Light Show from an old Transcontinental carriage transformed into a viewing car and placed on the turntable.

Another attraction in town is Peterborough’s Motorcycle and Antique Museum, which features more than 60 bikes including many imported European models. It’s well worth a visit to see the likes of a 1921 Yvels French racing bike, a 1959 Maserati Racer, and a 1975 Moto Guzzi Lemans.

By the closing years of the 19th century Peterborough was a prosperous place, reflected in the string of historic hotels and stores along the main street and buildings including a grand Bishop’s Palace.

The town's untouched 19th century buildings have cemented its classification as a historic town

PETERBOROUGH TO QUORN, 127KM

From Peterborough flat plains stretch away to the north-east on the 26km drive via gravel roads to Dawson, one of an array of ghost towns across the Southern Flinders Ranges that are legacy to the folly of early European settlers pushing north.

Along the way we see loads of kangaroos, lime-green parrots, flocks of screeching galahs, and a wedgetail eagle.

Dawson was a government town, established as part of an attempt to establish wheat farming north of Goyder’s Line. The town was surveyed in 1881, the Dawson Hotel built in 1883, and no less than three churches — Catholic, Primitive Methodist and Anglican — built soon afterwards.

Dawson once boasted several shops, a post office, school, Mechanic’s Institute, football oval, and a racetrack where annual races were held at this out-of-the-way place.

But extremes of weather and lack of water made life difficult for settlers. By 1960 all unsold allotments in Dawson had been purchased by the government, and the town sank into oblivion. The ruins of the hotel still stand on this eerie plain, as do abandoned churches, the hall, and not much else.

From Dawson we take the gravel Blackrock Road on the 42km drive to Orroroo, passing more abandoned homesteads, broken windmills and skeletal chimneys, all decaying dreams of settlers who gave up the struggle against a harsh environment.

Pausing at the Black Rock Lookout to take in sweeping views of flat tundra and the bluey-green hills of the Southern Flinders Ranges rising to the north, with a shock we see another vehicle — a farmer driving a ute. Traffic is few and far between out here.

Orroroo was officially named by George Goyder in 1875, when Solly's Hut, a log structure now used as a museum, was constructed.

A quiet agricultural town, Orroroo, population about 600, is home to a giant red river gum, which is situated on the northern side of Pekina Creek. Estimated to be more than 500 years old, this beauty has a width of about 10m.

From Orroroo we pass paddocks of swaying wheat on the 48km drive to Hammond, another ghost town, via Morchard.

The township of Morchard was laid out in 1877, with land set aside for suburbs, parklands, a school reserve, and half-acre town blocks. It failed, like so many others, and today all that’s left of Morchard is an old hotel, long-closed general store and church.

Hammond is another town that was supposed to become a thriving metropolis. Once home to 600 souls, it boasted a butcher, baker, post office, bank, school, hall, railway station, three churches, and no less than three general stores. Thirty men alone toiled at Barker’s foundry making buggies and drays. Today the wind whistles along dusty, empty streets, and a tumbleweed rolls across the road — just like the wild west.

Quorn, 40km north-west of Hammond, fared better than many towns in the region.

In January 1878 the first sod of the Great Northern Railway was turned and Quorn, which became another vital railway hub, was proclaimed in the same year. The railway line from Port Augusta to Quorn opened in 1879 and from there it was extended north to Marree in 1884, Oodnadatta in 1890, and Alice Springs in 1929.

Quorn grew into a busy place, reflected in the rich array of colonial architecture you see today, with a majestic pub on every corner, railway station, flour mill, courthouse, and rows of shops with shady verandas.

During World War II, Quorn was another key centre for troops who were moved by rail across Australia to Darwin and Papua New Guinea.

So quintessentially Australian is this charming town, population around 1300, that you may recognise parts of it — Quorn and surrounds has long been used by filmmakers, with movies filmed in the area including such classics as The Sundowners, Sunday Too Far Away, Gallipoli, The Shiralee and The Lighthorsemen. The latest is the blockbuster series The Tourist, filmed in April–June 2021.

Quorn is also home to the volunteer-run Pichi Richi Railway, regarded as one of Australia’s greatest heritage train journeys.

Visitors can ride in a restored timber carriage pulled by historic steam or diesel locomotives along the last operating section of the Old Ghan railway line, between Quorn and Port Augusta, 39km south-west.

The Pichi Richi, which runs from March to November, twists and turns around ochre-coloured embankments, climbs past landmarks such as Devil’s Peak, and crosses Waukarie Creek and the Pichi Richi Pass as it crawls along on half or one-day journeys. So popular is this much-loved train it’s wise to book in advance before you travel to Quorn.

Literal relics from the past

QUORN TO HAWKER, 66KM

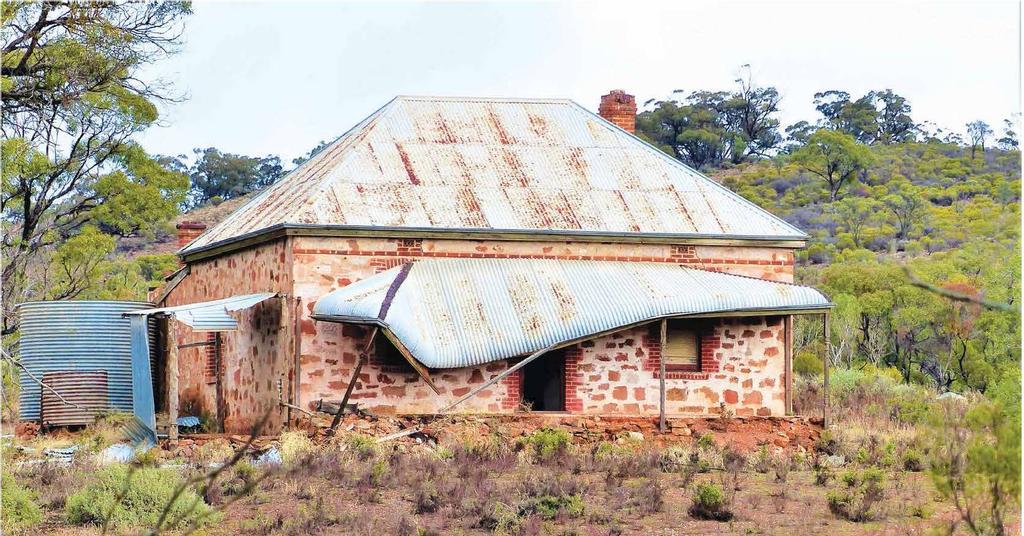

In this part of the world there are likely to be stone ruins over every hill and around every corner. In fact, there are so many that you almost become immune to the haunting beauty of the abandoned homesteads and ghost towns north of the Goyder Line.

But then you pull into sprawling Kanyaka Station, 40km north-east of Quorn, and it simply takes your breath away.

Established as a cattle and sheep station in 1851, workers battled the harsh climate at this remote place until Kanyaka grew to be the largest station in the district — at its peak, 70 families lived and worked here in what was like a small village. But severe droughts eventually caused this outpost to be abandoned in 1880.

The Great Northern Railway ran parallel to Kanyaka Station, and you can still see the raised roadbed of the old narrow-gauge railway today. Several new towns were established as the railway pushed through from Quorn to Marree including Wilson, 12km north-east of Kanyaka.

Wilson was established in 1881 in a flurry of excitement around the potential for wheat production: the town centre and more than 200 house blocks were surveyed, and just three years later Wilson boasted a general store, chapel, school, saddlery, a branch of the Commercial Bank, and the Gillick Arms Hotel.

Wilson soon went the same way as many other settlements, with lack of water causing many farmers to walk off their properties.

The last wheat crop was sown here in 1947, and the last resident left in 1954. Today all that’s left are a few ruins, including the stationmaster’s residence.

From Wilson it’s about 14km to Hawker, known as ‘the hub of the Flinders Ranges’ due to its location at the junction of roads from Port Augusta, Orroroo, Leigh Creek, Marree, Wilpena, and Blinman.

Another once-thriving railway town 3 until the Ghan line was relocated further west in the 1950s — Hawker, 378km north of Adelaide, has numerous heritage buildings, many built from corrugated iron. These days the tiny town is a base to explore this vast, rugged region — it’s 64km to Wilpena Pound and 70km to Lake Torrens.

Like so many places in the Flinders Ranges, Hawker, population around 300, is full of surprises, such as the Flinders Food Co.

Wandering into this welcoming cafe at three in the afternoon we discover it’s tapas time, when owner/chef Doogal Hannagan serves the likes of spicy buffalo wings, southern fried cauliflower with native dukkah, and fish tacos at a culinary oasis where the food rivals any upmarket city dining establishment.

The Southern Flinders Ranges are a place of magnificent beauty, with millions of years of geological history, thousands of years of rich Indigenous heritage, red-orange mountains, country towns oozing with history, night skies that are a blazing canopy of stars, and epic landscapes.

TRADITIONAL OWNERS